Another collectable identified.

By James Mulvey; posted June 3, 2019

View Original: Click to zoom, then click to magnify (1484 x 767) 507KB

|

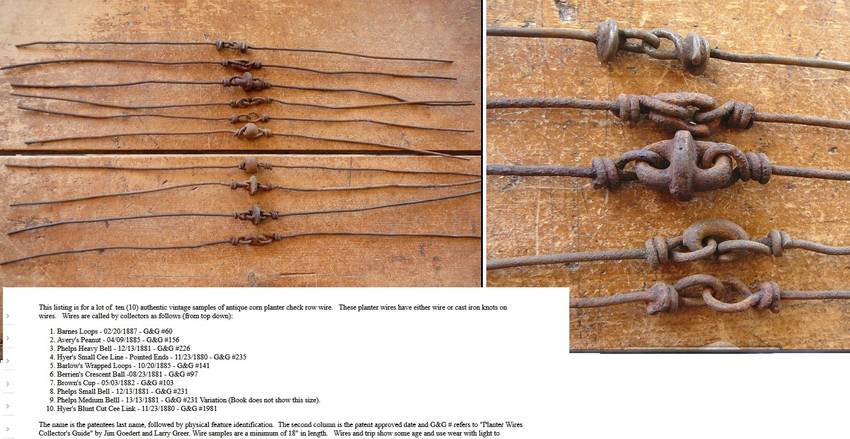

With over 100 views of the original posting, only two people knew what it was, Jim Colburn and Jack Snyder. From: Antique Barbed Wire Society treasabws@gmail.com What you have is called "Planter Wire" by collectors. It is also known as "Planter Check Wire". It's pretty interesting! Here are some notes from a talk that I gave on the subject. I hope it helps! ...... Mark Nelson As recently as 150 years ago, crops were hand-sown. A farmer could expect to plant an acre in one day. It's an image almost incomprehensible today: A farmer walking a plowed field, planting corn (or cotton, or potatoes, or other crops) by making seed holes with hoes, "dibble sticks," or simple drop devices, then manually covering and tamping each hole. By the early 1800s, though, mechanization became inevitable. Development of hand-pushed planters, then the horse-drawn drill-planter, and finally, the check-row planter, moved agriculture into a new era when, in 1852, George W. Brown, a carpenter from Saratoga County, New York, developed a check-row planter that enabled two men to plant 16 acres a day! The process worked like this: • Planter wire was stretched the length of a field. Tension on the trip wire was critical • A horse drawn cultivator or tractor was fitted with a "check-fork" which straddled the planter wire. • When the fork came to a knot in the planter wire a seed drop was activated by the knots or buttons on the wire as it passed through the planter fork. A tool on the back of the cultivator pushed dirt to cover the seeds. • Then the process was repeated on the next row. When done the wire was wound back up on a spool to be used in the next field or at the next planting. The knot on the check-line is an obstruction that caused a trip-lever to activate the seed drop mechanism. Sometimes a spoked, rimless wheel was used instead of a lever, with the knot engaging the spoke end to make the wheel rotate, in turn activating the seed drop. In both designs, the planter slipped past the knot, and the lever or spoke was readied for the next knot. Many types of knots were designed, including some which served as line connectors, throw-offs to drop or disengage the check-line from the planter when turning around, and to act as visual indicators for hand activating the seed dropper, or for hand planting. Check-line was made of single and multiple wire, cord (often with a small wire core), rope, chain and strip. Some check-lines were continuous, while others were chain-like. A single knot on the check-line, centered in an 18-inch length, is the standard specimen length. That length was chosen to prove patent features, so be careful not to cut longer lengths down too much. If the planter is all greased up and working well there are a few steps to get started with the planting. First, the check wire is staked into the ground at either end of the field and the wire is run through the planter. This wire has "blips" in it, where the planter will turn over and drop corn. The check wire drops about 3 seed every 40 inches (standard). As the horses pull the planter, the check wire makes a noise and turns a crank – which in turn deposits seed kernels into a furrowed row. At the end of every row the check wire is manually shifted so planting can begin on the next row. The long arm on the end of the planter marks where the tongue of the planter should go in the next row. It must be flipped, via rope, to the other side at the end of every row. Not all planters work like this. This process continues row after row until the field is planted. It is satisfying to look over a field of freshly planted corn and know that with a little rain, and a little sunshine, you will make something grow. By the turn of the 20th century, the implement was widely used. A corn report in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's 1903 Yearbook noted that "perhaps more corn is now planted by means of a check-rower than by any other device." Benefits of check-row planting Check-planter planting systems were designed to place hills of corn in checkerboard fashion, each about the same distance from its immediate neighbor. Thus a field could be cultivated first in the direction it was planted, later cultivated 90 degrees the other way, and finally, laid-by in the original direction. This was very effective for weed control, especially for tough ones like cockle-bur. Meanwhile, the usual objective of three corn plants per hill resulted in yields comparable to those achieved when using drills. A 1903 USDA report says hill dropping benefits were mostly due to cleaner cultivation, but drilled rows provided a more equal distribution of roots. Planter wire varieties were invented and patented by innovative farmers and inventors. They initially were made of rope, and later of steel. Like the invention of barbed wire, each inventor advertised their type of planter wire as the very best! Goedert and Greer report that the last patent evidence found of check-line use was issued in 1939 to C.K. Shedd, Ames, Iowa, for a 4-row planter. As late as 1952, the International Harvester Co. was still making the McCormick No. 240 2-row check-row planter. Check-row planter collectibles Early planters are difficult to find intact, except in some museums. But related items are available and avidly sought by collectors. Plus, lots of planter literature, drawings and photographs – collectibles in themselves – are also available. Paper items include patent descriptions and illustrations, advertising materials and educational articles and booklets. Popular planter items include planter plates, seedbox lids and wrenches. Check-planters have their own related collectible items, including check-line rope and wire, anchors, reels, tighteners and planter parts. Goedert and Greer write that the knot or tripping device on a section of check-line is the object most collectors seek. Check-lines can be mounted on small boards or cut-out sticks for display such as that used by barbed wire collectors. About 200 knot designs are available to the collector. Remembering check-row planting While it's difficult to find farmers who've actually check-planted, collectors and restorers congregate at antique farm shows |